Core

Business World, 1 April 2014

Before 2007 non-governmental organizations (NGOs) were the partners of government. They sat in the procurement bids and awards committees (PBACs), helped monitor project implementation, and participated in identifying community needs for planning and budgeting purposes.

In recent years, the NGOs’ role has changed. They’re now actively involved in project implementation and thus have direct access to public funds.

For NGOs, having direct access to public funds is out of character. They are supposed to raise their own money to finance projects that would benefit their local constituencies.

The glow of giving is more meaningful if the money used to fund their community activities were sourced from the traditional sources — donations from international organizations, private sector philanthropists, fund raising campaigns, etc. — and not from government coffers.

Much of the corruption associated with the NGO scam could have been avoided had the NGOs stuck to their traditional roles instead of getting involved as contractors for activities and projects funded in the national or local budgets.

The non-existent projects supposedly implemented by some true and some fake NGOs could have been avoided had the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) and the implementing agencies been more conscientious, prudent, and careful in exercising their respective duties.

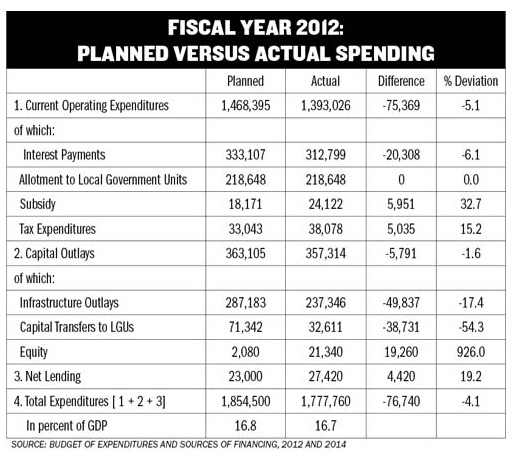

The DBM has abused its power by deviating almost at will from the spending program authorized by Congress. It was in 2012 that a huge chunk of discretionary spending took place as part of the controversial Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP).

In 2012, Congress authorized the President to disburse P18.2 billion for subsidy. Yet, the Executive Department spent P24.1 billion, an increase of P6 billion, or a 32.7% percentage deviation.

In 2012, Congress authorized the President to spend P2.1 billion for equity. Yet, he spent P21.3 billion, an increase of P19.3 billion, or a 926% percentage deviation.

How much of this discretionary spending is legal and how much is illegal? This question would have been easy to answer if there were a Freedom of Information (FOI) Act in place. No wonder the Aquino III administration has moved heaven and earth to derail the passage of the FOI bill!

CONDITIONS FOR TRANSFER OF PUBLIC FUNDS TO NGOS

Strictly speaking, the General Appropriations Act (GAA) allows the transfer of funds (not only Priority Development Assistance Fund, PDAF) to civil society organizations (CSOs), NGOs or people’s organizations (POs) as implementors of programs and projects but under well-defined conditions.

First, the transfer should follow the rules defined in Resolution No. 12-2007 of the Government Procurement and Policy Board. The rules where issued in response to the provision in the 2007 GAA allocating P250 million for the construction of buildings that was made available to NGOs, including the Federation of Filipino Chambers of Commerce and Industry, Inc. (FFCCII). These have been the most authoritative rules on the use of NGOs as service providers or contractors.

Second, the NGO should have an established track record of service delivery and should be financially stable. The rules require the submission of “audited financial statements for the past three years, stamped ‘received’ by the Bureau of Internal Revenue or its duly accredited and authorized institutions, for the immediately preceding calendar year, showing, among others, its total and current assets and liabilities.”

Third, the GAA requires that fund transfers to CSOs shall be made only when earlier fund releases, if any, availed of by the CSOs shall have been fully liquidated pursuant to pertinent accounting and auditing rules and regulations.

STRICT BUDGET RULES

The DBM and the implementing agencies are bound by strict budget rules on budget releases and project implementation.

Funds, whether from the unconstitutionally declared PDAF or other sources of appropriations are always released to an implementing agency (IA) which could be a department, an agency, or a local government unit. Funds are never released to an NGO.

The choice of the NGO as the implementing service or supply contractor is the responsibility of the agency head — not the senator or congressman, even in the case of PDAF or other off-budget public funds. The contract cannot be provided to an NGO at the whim and caprice of the head of the implementing agency.

If the legislator insists on awarding the service/supply contract to his chosen supplier or contractor, it is the responsibility of the head of the IA to advise the legislator that it can’t be done since it would violate some existing rules, mainly the Government Procurement Reform Act.

An honest bureaucrat shall not follow an illegal act.

A general provision in the GAA requires that a “report on the fund releases indicating the names of CSOs shall be prepared by the agency concerned and duly audited by the Commission on Audit, and shall be submitted to the Senate Committee on Finance and the House Committee on Appropriations, either in printed form or by way of electronic document.”

The report shall be the audited by the Commission on Audit (COA), not by any private auditor or firm. It is the responsibility of the head of the IA to require no less than an audit by the COA.

Has the COA audited the concerned IAs? Has the agency concerned submitted the COA-audited reports to the Senate Committee on Finance and the House Committee on Appropriation?

What have these two powerful congressional committees done to the reports? Reviewed or promptly referred them to the archives where they might quickly fade into oblivion.